NIGERIAN Afrobeats legend, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, will posthumously receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys, almost three decades after his death at the age of 58.

“Fela has been in the hearts of the people for such a long time. Now the Grammys have acknowledged it, and it’s a double victory

“It’s bringing balance to a Fela story,” his musician son, Seun Kuti, told the BBC.

Rikki Stein, a long-time friend and manager of the late musician, said the recognition by the Grammys is “better late than never.

“Africa hasn’t in the past rated very highly in their interests. I think that’s changing quite a bit of late.”

Following the global success of Afrobeats, a genre inspired by Fela’s sound, the Grammys introduced the category of Best African Performance in 2024.

This year, Nigerian superstar Burna Boy also has a nomination in the Best Global Music Album category.

But Fela Kuti will be the first African to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award, albeit posthumously. The award was first presented in 1963, external to American singer and actor, Bing Crosby.

Other musicians who will receive the award this year include Mexican-American guitarist, Carlos Santana, Chaka Khan, the American singer known as the Queen of Funk, and Paul Simon.

Fela’s family, as well friends and colleagues, will be attending the Grammys to receive his award.

“The global human tapestry needs this, not just because it’s my father,” Seun said.

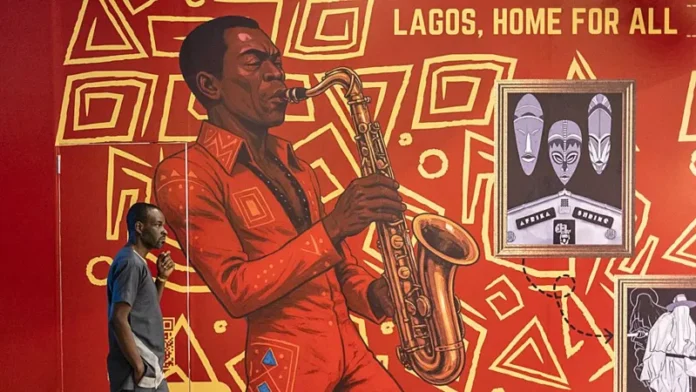

Fela is indelibly linked to Lagos, where his performances at the Afrika Shrine club were legendary

Stein said it is important to recognise Fela as a man who championed the cause of people who had “drawn life’s short straw,” adding that he “castigated any form of social injustice, corruption [and] mismanagement” in government.

“So it would be impossible to ignore that aspect of Fela’s legacy,” he told the BBC.

Fela Kuti was not simply a musician, but also a cultural theorist, political agitator and the undisputed architect of Afrobeat, which is distinct from, but ultimately led to the modern sound of Afrobeats.

He pioneered the Afrobeat genre, alongside drummer, Tony Allen, blending West African rhythms, jazz, funk, highlife, extended improvisation, call-and-response vocals and politically charged lyricism.

Across a career spanning roughly three decades until his death in 1997, Fela released over 50 albums and built a body of work that fused music with ideology, rhythm with resistance and performance with protest.

His music incurred the wrath of Nigeria’s then-military regimes. In 1977, after the release of the album, Zombie, which satirised government soldiers as obedient and brainless enforcers, his compound in Lagos was raided.

Fela’s music resonated with people across Africa and the Diaspora. Known as Kalakuta Republic, the property was burned, residents were brutalised and his mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, later died from injuries sustained during the assault.

Rather than retreat, Fela responded through music and defiance. He took his mother’s coffin to government offices and released the song, Coffin for Head of State, turning grief into protest.

His ideology was a blend of pan-Africanism, anti-imperialism and African-rooted socialism.

Fela’s mother was hugely influential in his life, helping shape his political consciousness, while the US-born singer and activist, Sandra Izsadore, helped sharpen his revolutionary outlook

Born Olufela Olusegun Oludoton Ransome-Kuti, he dropped Ransome because of its Western roots.

In 1978, he married 27 women in a highly publicised ceremony, bringing together partners, performers, organisers and co-architects of the cultural and communal vision of Kalakuta Republic.

Fela endured repeated arrests, beatings, censorship and surveillance by the security forces. Yet, repression only amplified his influence.

“He wasn’t doing what he was doing to win awards; he was interested in liberation, freeing the mind.

“He was fearless. He was determined,” Stein recalled.

Fela’s musical evolution was shaped not only by Nigeria, but also by Ghana. During the 1950s and 1960s, highlife music, pioneered by Ghanaian musicians, such as ET Mensah, Ebo Taylor and Pat Thomas, became a defining sound across West Africa.

Its melodic guitar lines, horn sections, dance rhythms and cosmopolitan identity deeply influenced Fela’s early musical direction.

He spent time in Ghana absorbing highlife’s structure, horn phrasing and dance-oriented arrangements before fusing it with jazz, funk, the rhythms of his own Yoruba people, and political storytelling.

The DNA of highlife can be heard in Afrobeat’s melodic sensibility and its balance between groove and sophistication.

In this sense, Afrobeat is not only Nigerian; it is West African, pan-African and Diasporic in origin, carrying Ghana’s musical imprint at its foundation.

On stage, Fela cut an unmistakable figure. Often bare-chested or draped in the wax-printed fabric popular across West Africa, hair shaped into a crisp Afro, saxophone in hand, eyes alert with intensity, he commanded a large band of over 20 musicians.

His performances at the Afrika Shrine in Lagos were legendary, part concert, part political rally, part spiritual ceremony.

Stein recalled that performances at the Shrine were immersive, rather than conventional: “When Fela played, nobody applauded.

“The audience wasn’t separate. They were part of it.”

Music was not spectacle; it was communion.

Fela will be the first African to receive the Lifetime Achievement Award.

His identity was shaped in part by artist and designer, Lemi Ghariokwu, who created 26 of his album covers between 1974 and 1993.

Ghariokwu, while welcoming the posthumous award, told the BBC: “Fela has been an ancestor for 28 years. His legacy is growing by the day. This is immortality.”

Today, Fela Kuti’s music is still popular with millions around the world and his influence is audible in modern artists, such as Burna Boy, Kendrick Lamar and Idris Elba.

Elba is a huge fan. The award-winning actor and DJ has curated an official vinyl box set, Fela Kuti Box Set 6, and has publicly compared him to icons, such as Sade and Frank Sinatra, to illustrate the point that Fela has his own unique sound.

Fela Kuti performed at major international festivals in Europe and North America, introducing global audiences to a bold and politically charged version of modern Africa.

“I didn’t even realise my dad was famous. That’s credit to him. He kept me grounded,” Seun said.

Seun, who was just 14 when his father died, added: “Fela never made me feel like I was a child.

“He didn’t hide anything from me; he talked about everything openly.”

What stayed with Seun most was not spectacle, but discipline, clarity and humanity, noting: “The human part of him, leadership, musicianship, fatherhood, that was the epitome of who he was.”

One of Seun’s most revealing reflections speaks to independence and identity: “Fela was our dad, but you didn’t own him. Fela belonged to himself. But we all belonged to him.”

Fela insisted on being addressed by name, not by title, even by his children. Seun recalled having his pocket money docked after calling him, “Pops,” a moment that carried a lesson in respect.

“He always reminded us that he was in service to others more than himself.”

That ethic shaped Seun’s evolution from youthful ambition toward cultural responsibility. “I used to make music to make money. But as I’ve grown, I lean more toward working for my people, as well as my art.”

Fela led multiple ensembles, most famously Africa 70 and later Egypt 80, the latter now carried forward by his son.

These were not conventional backing bands; they were musical militias, trained in discipline, endurance and ideological purpose.

Stein recalled Fela’s obsessive attention to detail, noting: “He tuned every instrument personally. Music wasn’t entertainment to him; it was his mission.”

Afrobeats Legend, Fela, Becomes First African Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award Winner

Published: